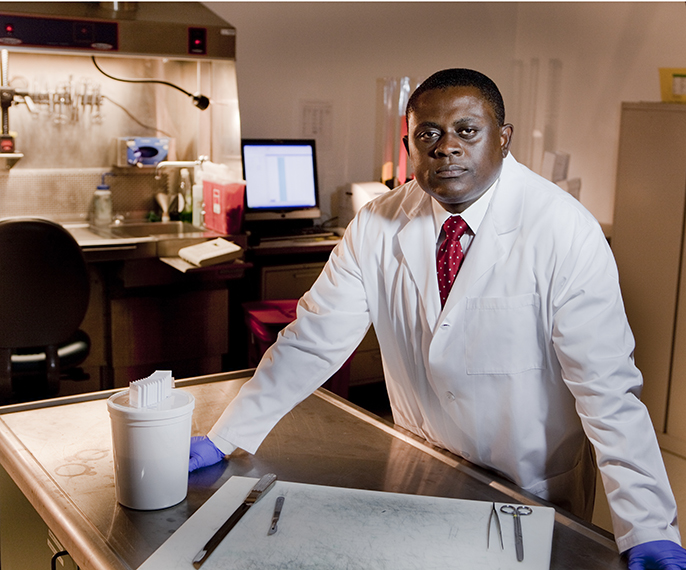

Dr. Bennet Omalu, a Nigerian-born forensic pathologist, who discovered the brain trauma that is part of football for many players. (universityofcalifornia.edu)

“Can you take the head out of a high impact contact sport? No!”

By Jamiles Lartey

The Guardian (12/28/15)

The film begins much like the real story, with number 52: Iron Mike Webster.

The day he was inducted into the NFL hall of fame, Webster, a Pittsburgh Steelers legend and stalwart center of one the greatest dynasties in league history, was at the beginning of a very public unravelling. It was late July 1997 in Canton, Ohio, and Webster’s acceptance speech rambled and dragged, running beyond his allotted time by a good 13 minutes. It wasn’t without its lucid moments, though. “You know it’s painful to play football, obviously,” Webster said. “Two a day drills in the heat of the summer and banging heads. It’s not a natural thing.”

Five years later, at age 50, Webster was dead, of an apparent heart attack. The man scheduled to perform his autopsy might have known less about Iron Mike than anyone in the city of Pittsburgh. Bennet Omalu, a Nigerian-born forensic pathologist, only knew what he’d seen on television earlier that morning, that this favorite son of the steel city was disgraced – sleeping in his truck, estranged from his wife, busted for forging prescriptions.

Acting on a whim

As he moved through the examination, weighing, measuring, and testing, eventually Omalu arrived at Webster’s brain. When he opened the skull, Omalu was surprised to find that by all outward appearances, it was completely normal. On a whim he ordered an assistant to “fix the brain”.

Over the ensuing decade, that decision would bring Omalu face to face with the billion-dollar National Football League and its army of lawyers, doctors and public relations experts. The conclusion he would come to, that the human brain cannot withstand an unlimited number of traumatic impacts, presented a profoundly inconvenient truth for America’s game.

(Daily Call cartoon by Mark L. Taylor, 2015. Open source and free to use with link to www.thedailycall.org )

Omalu’s research suggested that eventually the collisions, large and small, which characterize a contact sport like football take their toll. Speaking to the Guardian in New York, Omalu said: “There is no equipment that can prevent this kind of injury.”

Now that his findings are mainstream, in the form of the just released movie Concussion starring Will Smith, the future of the game is more in doubt than ever.

One of the first things Omalu noticed about Webster’s body was the hardened calluses on his forehead, a shelf of scar tissue, right about where the – in those days – thin, stiff padding of his helmet would be thrust into Webster’s face on every snap. There was no shortage of damage to discover. Ever the embodiment of lunchpail Pittsburgh tough, Webster, in his last year, had begun repairing his body in blue collar fashion: spit and glue. Literally. Webster had taken to reattaching his teeth with super glue, and using it to plug his wounds. He was using duct tape to make walking on his cracked, disfigured feet bearable.

And Iron Mike’s psychiatric deterioration was at least on pace with what was happening to his body. Webster was scarfing down ritalin like candy; it was the only thing that could steady his mind enough to perform daily tasks. He was afraid to fall asleep, and yet took to shooting himself with a stun gun just to pass out.

Empathy

Omalu, too, knew what it was like to be psychiatrically unwell. In college, which he began at age 16 at the University of Nigeria Enugu, Omalu began to experience profound bouts of depression. In Jean Marie Laskas’s book Concussion, Omalu describes feeling unable to move, unmotivated to do anything. “Something was wrong inside me, very, very wrong,” he said.

Omalu told the Guardian that this experience with psychiatric illness, at a time in Nigeria when the very idea was generally regarded as disgraceful, played a major role in how he approached Webster that September day in 2002. “When I met Mike Webster in death, that morning I had heard about his life. I empathized with him. I saw myself in Mike. What it is to be psychologically ill and have people not understand,” Omalu said.

“It was one of the factors that converged to help me unravel this disease,” Omalu added. “There was this camaraderie between me and Mike, so I said to him: ‘Let’s figure this out together, there’s something wrong.’”

Omalu didn’t know what he was looking for when he asked that Webster’s brain be fixed, the chemical process that solidifies the organ enough to be sliced and examined. But Omalu was certain that “people don’t go crazy for no reason”, Jeanne Marie Laskas wrote in Game Brain, the 2009 GQ article which spawned both the book and the movie Concussion.

After Omalu had the slides made, spending tens of thousands of dollars of his own money, he finally made a key discovery: pathological buildup of a protein called tau. While tau belongs in a healthy brain, too much and the proteins tangle up and strangle off healthy cells. In the film, Smith’s character describes it as like pouring concrete down plumbing pipes. These tau tangles had been seen before, in boxers, part of a condition known as dementia pugilistica, or punch-drunk syndrome. This was the first time, however, that it had been seen in the brain of an NFL player.

“After a certain number of blows to your head, nobody knows exactly what number, your brain resets itself and begins to initiate abnormal biochemical cascades that result in the buildup of abnormal proteins like tau. So by the time tau is accumulating, the injury is already done,” Omalu said. …