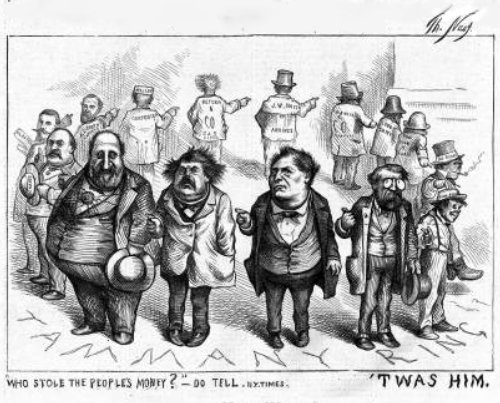

Cartoon by progressive reformer cartoonist Thomas Nast. (www.superteachertools.us)

(Editor’s Note: Know thy history. There is hope. — Mark L. Taylor)

By Heather Cox Richardson

Salon (9/8/15)

Why is Donald Trump so popular? He has captured the moment when voters recognize that Republican political rhetoric has nothing in common with reality. Trump brings rhetoric and reality together in a cartoon caricature of a Republican politician that anyone can understand. That gives him a vital role in history. He is the perfect exorcist to drive a stake through the heart of the modern Republican Party. But he is not the first in history to perform this operation. The same crisis hit the party in the 1890s.

When it was over, the nation had a reformed Republican Party, and a new historical era.

Today’s Republican Party is enslaved to Movement Conservatism, and Trump trumpets the rhetoric of that movement in crude sound bites. Since the 1950s, Movement Conservatives have been determined to roll back the business regulations of the New Deal. But those protections are popular. So to undermine them, Movement Conservatives hammer home the idea that legislation protecting workers, people of color, or women is socialism, a con that sucks money out of the pockets of hard-working whites and siphons it into the pockets of grasping workers, shiftless blacks, or slutty women.

Movement Conservatism was a fringe force from the 1950s until the 1980s, when voters elected Movement Conservative Ronald Reagan to the White House. But even then, their control of the Republican Party was not a given. In 1982, Movement Conservatives’ slashing of $35 billion from the budget in the midst of a cash crisis crashed the economy and drove unemployment to its highest rate since the Depression; a 40% increase in defense spending revived the economy but created a skyrocketing national debt. Republican support wavered, and movement leaders clung to power by bringing in new voters. In 1986, anti-tax activist Grover Norquist, a former economist for the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, created an army of evangelical voters to boost the numbers behind Movement Conservatism. He promised born-again voters pro-life and pro-Christian activism so long as they lined up behind big business economic policies.

Trump presents a crude version of these Movement Conservative themes. His vile language about minorities and women is simply a different octane of the Movement Conservative gasoline, an emotional explosive used by every one of the other sixteen candidates for the Republican nomination. It is a simple idea: that “takers” want a handout. Similarly, while observers have expressed surprised that the thrice-married, non-churchgoing Trump attracts more support from evangelical voters than, say, the aggressively religious Mike Huckabee, that support reflects a Movement Conservative pattern established a generation ago.

But Trump’s danger to the Republican Party is not simply that he rips the veneer off the racism, sexism, and religious hypocrisy of Movement Conservatism, exposing its rhetoric about taxes and lazy takers for the elitism it is. Trump also articulates the anger of a generation of voters who see that they have been taken for a ride. Movement Conservatives promised voters who were falling behind in the modern world that if they voted Republican, tax cuts and a smaller government would create a roaring economy and they would prosper.

In fact, the opposite was true. Since 1980, tax cuts have not actually lowered taxes; they have moved them from the wealthy onto poorer Americans. The deregulation of the economy has indeed redistributed wealth—upward. Today the top 1 percent of families takes home more than 20% of income and own as much wealth as the families in the bottom 90%. Fracking and drilling have polluted drinking water and oceans. Cuts to education and student loan rates have threatened poor Americans’ ability to rise. When the Supreme Court handed down the Citizens’ United ruling, it seemed to codify the principle that the rich should own the country. Donald Trump doesn’t simply echo the racism and sexism of the last several decades, he calls—in his loose, vague way—for a fairer tax code and for tariffs to protect American workers. Even more important to his supporters, he is outside politics as usual. He is outside a system that has been bought and paid for by businessmen.

Trump is a populist in the same mold as the nineteenth-century Populists who gave their name to American grassroots political movements. Historians and pundits argued themselves blue in the face over whether Populists were reactionary or progressive, but they were both. Then, as now, the Populists embodied a moment when reactionary rhetoric finally tore open to reveal a brutal truth: that the rhetoric did not reflect reality. When that moment happened, people who still believed in the bugbears they had been taught to hate also demanded that government policy actually engage the real world.

During the Civil War, the fledgling Republican Party constructed the nation’s first activist government, using taxes to fund social welfare legislation for the first time in American history. Their policies were enormously popular, but in the wake of the Civil War, businessmen joined with white racist Democrats to argue against government activism. Laws protecting the ability of workers and black men to rise were, they argued, a redistribution of wealth. Business regulation and federal protection of black rights required a bureaucracy paid for with white tax dollars. Schools, hospitals, roads, and public buildings also meant tax levies to pay for infrastructure, an infrastructure used primarily by Americans who could not afford to pay for those luxuries themselves. By the 1870s, big-business Republicans leveraged white fears of immigrants and hatred for black Americans to retain control of the government. Democrats who advocated laws that would regulate business were socialists, Republicans insisted. They were intent on redistributing wealth from hardworking white men to lazy immigrants and African Americans. On the Republicans’ watch, the late nineteenth century became the era of the “robber barons,” when monopolies and trusts ran the government with the sole intent of protecting big business. Under Republican policies, wealth moved upward, creating an era historians later dubbed the Gilded Age.

But the Republicans’ image of a prosperous world endangered only by the Democrats and the people the Democrats represented—workers and minorities desperate for a handout—started to splinter as Republicans’ own voters began to suffer. Wages stagnated while monopolies colluded to raise prices; cities were polluted by businesses that dumped poisons into neighborhoods; men died in workplace accidents for which employers paid no indemnity, leaving families destitute; middle-class children died from contaminated food; impoverished farmers forced to pay exorbitant railroad rates were told they were lazy and should work harder. Democrats began to win national elections; Republicans howled that the Democrats were triumphing only by fraud and corruption.

But the public did not buy this claim. By 1890, the protests against Republican government had spread beyond the Democrats and into an upstart movement of farmers’ “Alliances.” Its leaders warned that “Wall Street owns the country…. It is no longer a government of the people, by the people, and for the people, but a government of Wall Street, by Wall Street, and for Wall Street.” In that year, as Republicans passed even stronger pro-business legislation with the promise that it would, this time, bring back prosperity, voters gave the Democrats a two-to-one majority in the House. Republicans held the Senate only because they had jiggered the Electoral System by adding six new Republican states to the Union in the year before the election.

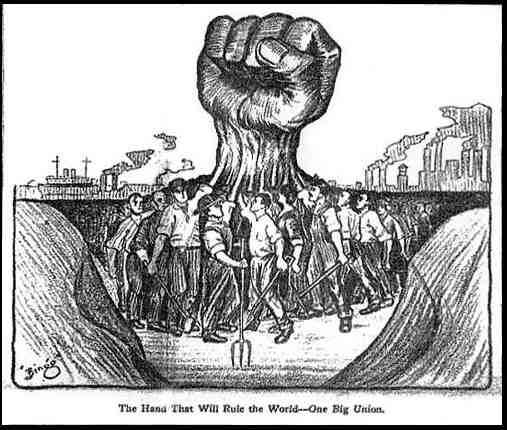

The Populists organized the following year. They embraced the reactionary anti-immigrant and often racist sentiments of the Republicans, the arguments Republican leaders had used to rail against wealth redistribution. But Populists turned upside down the idea that Americans must guard against government policies that redistributed wealth. Rather than apply accusations of redistribution only to the poor, Populists turned it against the rich. Wealthy men, they warned, had brought the nation to “the verge of moral, political, and material ruin.” Because they believed that government was hopelessly corrupt and that newspapers were either shills or muzzled, some of the Populists parroted strange conspiracy theories: one clownish leader advanced the ideas that Atlantis was a lost civilization and that Francis Bacon was the real author of Shakespeare’s works. But the Populists’ distrust of authority came from their recognition that they had been sold a bill of goods. The capital generated by the vast majority of Americans, their platform noted, was stolen to build up colossal fortunes for a few rich men who despised the republic and endangered liberty. “From the same prolific womb of governmental injustice we breed the two great classes—tramps and millionaires,” their platform read. Crucially, the Populists were not Democrats: They condemned both parties. Party leaders on both sides, their platform announced, were willing “to destroy the multitude in order to secure corruption funds from the millionaires.”

(Heather Cox Richardson is the author of “To Make Men Free: A History of the Republican Party,” amongst several other books, and a professor of history at Boston College.)