While America’s CEOs have seen their compensation soar in the past six years, the average annual earnings of employees haven’t budged.

By Suzanne McGee Guardian UK (6/25/15)Psst … want to earn a CEO’s hourly wage? You can. You’ll just have to toil for about five weeks to do it, without a single day off.

According to the latest annual survey by the Economic Policy Institute, a progressive think tank, CEOs at the 350 largest companies in the country pocketed an average of $16.3m in compensation each last year. That’s up 3.9% from 2013, and a whopping gain of 54.3% since the recovery began in 2009.

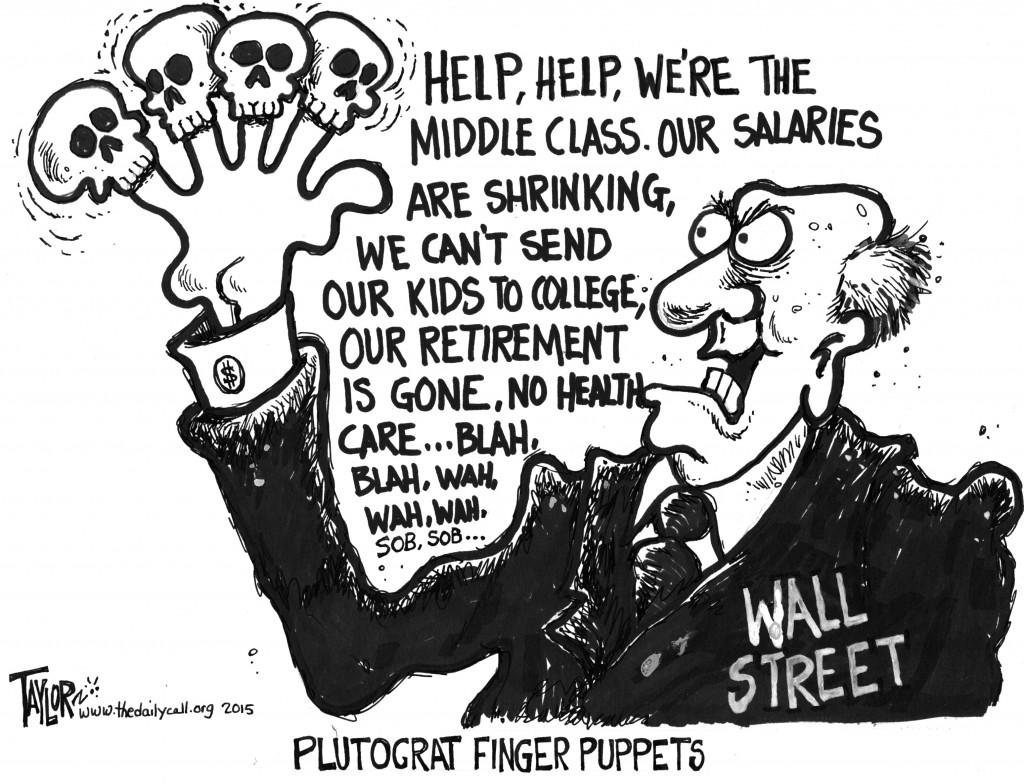

The average annual earnings of employees at those companies? Well, that was only $53,200. And in 2009, when the recovery began? Well, that was $53,200, too. In other words, while the CEOs have seen their compensation soar by 54%, the typical worker’s paycheck hasn’t budged.

You’d expect to see a gap between the earnings of the guy who is responsible for running the business and those that work there, of course; that would just reflect the greater burden on the former for keeping the whole show on the road (and the fact that if he doesn’t, his tenure can end very rapidly). Then, too, a CEO often is either a senior industry executive with considerable experience or, in the case of a smaller business or startup, its founder, who has put his own capital and reputation on the line to get the company going and keep it afloat.

But it’s the size of the gap that is the real problem, especially when set against the stagnation of employee salaries.

Right now, the average CEO compensation package is 303 times the size of the average earnings of their employees. The late management consultant Peter Drucker (who, as a winner of the Presidential Medal of Freedom, was no foe of capitalism) recommended that a CEO-to-worker pay ratio should never top 25; otherwise, he argued, they would “increase employee resentment and decrease morale”. By 2005, when Drucker died, the ratio was closing in on 400:1.

Employee resentment? Check. Low morale? Check. But neither has mattered much to the compensation committees signing off on CEO packages – and still failing to disclose publicly the size of their specific gap. While the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act required companies to provide information on the CEO pay ratio to their investors (and thus, to the general public), and the Securities and Exchange Commission made a specific proposal about how that might be handled, opposition has ensured that so far, it hasn’t seen the light of day.

Shareholders – the folks in a position to push for this to happen – don’t seem to put altering this state of affairs at the top of their wish lists. Perhaps that’s because they, unlike the employees stuck with wages that have flat-lined, are enjoying profits of their own, in the form of soaring stock prices. Six years into the bull market, stock indexes have continued to set new records this year, with even the Nasdaq Composite Index posting new all-time highs, finally breaking above the levels it recorded in the dotcom bubble years.

As one 2005 academic study found, investors – whose representatives on the board of directors have the final say on CEO compensation – seem to become complacent during bull markets, indifferent to how rich CEOs, too, are getting, as long as they are sharing in the riches.

Of course, the bull market also is one of the reasons for those big paydays for CEOs. In fact, it’s probably the single largest reason for the explosion in the CEO pay gap. In 1978, when the idea of giving a CEO the majority of his compensation in the form of stock was almost non-existent, that CEO earned about 30 times what his average employee did. By 1989, when the idea of stock-based compensation was gaining traction (and activist investors and corporate raiders were taking aim at corporate managers they considered fat, lazy and unmotivated to increase returns for shareholders), the figure was closing in on 60. By 2000, getting a significant portion (or most) of one’s compensation in stock, option grants or deferred grants of equity was standard, and the gap was 376, according to the EPI.

Consider the controversial pay package that Jamie Dimon earned in 2014, for the bank’s 2013 performance. JP Morgan Chase’s board awarded him $20m that year, or less than $1m for every $1bn in regulatory fines and penalties that the bank had to pay. But defenders of the pay package pointed out that of that sum, $18.5m was in the form of restricted stock grants, which the board could cancel later, if other problems emerge. This year, Dimon got the same $20m, of which only $1.5m was in the form of a salary - $7.5m came in the shape of a cash bonus and $11.1m in restricted stock.

You can’t separate the question of CEO pay from the stock market. Rewarding with CEOs stock and options provides them with an incentive to boost the stock price – and it conserves cash. If the company has to issue more stock down the road to swap those options for shares in the business – something that existing shareholders usually don’t like – the idea is that by then the shares would have gone up in value so much that grumbling would be minimal.

And that has spilled over into the broader wage gap. The more affluent you are, the more likely you are to own stocks – and to have participated in the post-2009 stock market rally, and to have become wealthier from your investments, even if your salary was stagnant. If you lost a job during the recession and remained unemployed, or never earned enough to invest at all, then you couldn’t afford to buy at the bargain basement prices in the spring of 2009, and may even have had to sell at that time in order to cover mortgage payments, pay college tuition for your kids, or buy groceries. In contrast, wealthier families, with more of a cash cushion, could afford to set aside spare money to continue investing. Studies have shown that these phenomena have resulted in the top 1% getting richer, and doing so at the expense of the rest of us. The authors of those studies, meanwhile, argue that’s not good for the economy, since the CEOs and others don’t add economic value in exchange for all their extra riches.

Some of those who have campaigned for higher minimum wages celebrated when Walmart announced it would boost its starting wage to at least $9 an hour. The problem, as Ralph Nader pointed out two years ago, is that Walmart’s CEO made (at that point) $11,000 an hour. The bigger problem is that we even deceive ourselves about how big this wage gap is. The biggest problem of all is what to do about it.

In the short term, if stock ownership is the route to affluence or financial security, and given that Americans are woefully unprepared for retirement, why shouldn’t companies routinely supplement their employees’ salaries with stock bonuses in the same way that they do those of their CEOs? Why not grant a Walmart employee 100 shares of stock at the end of every calendar year, in some kind of retirement account?

If that idea is too daring, employees and shareholders could at least push for their companies to disclose the CEO pay gap, as provided for in the Dodd-Frank Act, and to explain why they shouldn’t earn a mere 100 times the salary of their employees.

My favorite idea, however, is for an individual shareholder to stand up at each annual meeting next spring, and ask the CEO to describe what they do in a typical hour of their working day. The follow up question, of course, would a request for the CEO to explain just why that’s worth (based on the very generous assumption that they’re working 10 hours a day, 365 days a year) about $18,607, each and every hour, according to the EPI data. The answers might be risible; they might be revelatory. They’ll certainly fuel future debate and discussion.